Update: two new studies published in February 2022 provided additional insight into the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in deer and the potential risk to hunters. As part of our commitment to keeping our members informed on this evolving issue, we have updated this article to reflect this new information.

The Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry (NDMNRF) had previously reported that the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) had been detected in five white-tailed deer in the London, Ontario area. Those detections marked the first time the virus has been detected in wildlife in Ontario, though similar detections have occurred in white-tailed deer in Quebec (Kotwa et al., 2022), Saskatchewan, and several American states.

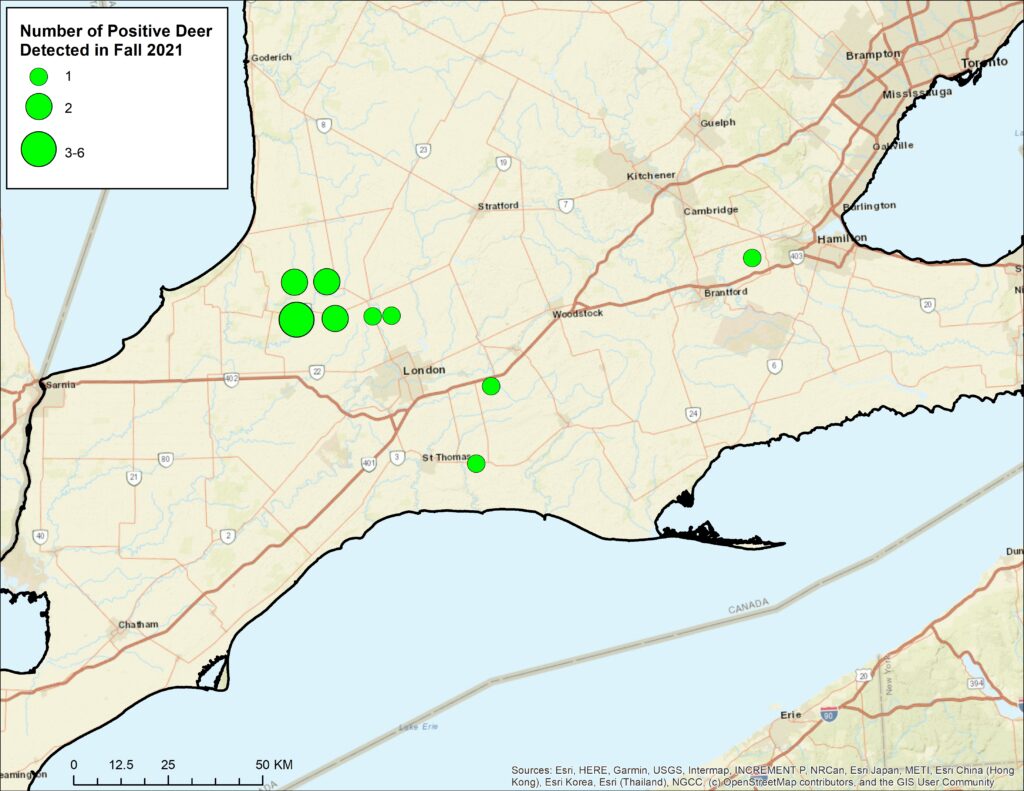

According to a preprint article (Pickering et al., 2022) published online on February 25th, and which included NDMNRF authors, additional testing revised that number, with 17 out of 298 deer testing positive for SARS-CoV-2. These seventeen cases were found during the NDMNRF’s 2021 chronic wasting disease (CWD) surveillance program with 249 samples coming from southwestern Ontario and 51 samples coming from eastern Ontario (note that two of the deer collected were not successfully tested). All positive cases were detected in southwestern Ontario with all eastern Ontario deer testing negative.

The map below (reproduced from Pickering et al., 2022), shows the approximate locations where the positive deer were found.

What do we know about SARS-CoV-2 in deer?

The virus that causes COVID-19 is a zoonosis which is a disease that has spread from animals to humans. This animal link, and findings of the virus in various captive wildlife early in the pandemic, led scientists to investigate the susceptibility of various species to the virus.

Early research identified white-tailed deer as a potentially susceptible species (Damas et al., 2020), while experiments conducted on captive deer found that deer could become infected with the virus and could pass it on to other deer (Palmer et al., 2021). Field studies, which often coincided with existing deer population reduction programs or CWD surveillance programs, detected evidence of the virus among free-ranging deer. Antibody testing of deer in Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania found that 40% of samples from 2021 showed evidence of exposure to the virus (Chandler et al., 2021). Genetic testing among free-ranging and captive deer in Iowa from September 2020 to January 2021 detected the virus in approximately 33% of samples and found it in a pattern that strongly suggested multiple instances of human-to-deer spread as well as deer-to-deer transmission (Kuchipudi et al., 2021). Human-to-deer and deer-to-deer transmission was also found in a study that swabbed and tested deer in northeastern Ohio from January to March 2021 (Hale et al., 2021). This study detected the virus in almost 36% of samples and found that the prevalence of the virus among deer was highest in areas adjacent to higher human population density.

Hale et al. (2021) found that male deer and heavier deer were more likely to test positive. In contrast, Pickering et al. (2022) and another study that tested deer in Pennsylvania (Marques et al., 2022) both found more positive cases among female deer than male deer. At this point it is not clear what, if any, impact sex has on the chances a deer becomes infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Both Pickering et al. (2022) and Marques et al. (2022) provided evidence that suggests that the virus has been circulating among deer populations for an extended period of time. The virus found among deer in southwestern Ontario most closely resembled a version of the virus that was sampled in humans in Michigan in November and December 2020. In Pennsylvania, some of the deer that tested positive in November 2021 were infected with the Alpha variant, months after the Delta variant had displaced the Alpha variant among humans in the state. In both studies, the virus in deer had numerous differences from the human version, which further supported the idea that it had been circulating among deer for some time.

In all these studies, as well as ongoing surveillance programs, there has been no evidence that the virus is harmful to deer. All infected deer have appeared healthy and there have not been any reported cases of deer dying from the virus. While studies (Hale et al., 2021 and Kuchipudi et al. 2021) have documented human-to-deer spread of the virus by matching the variants of the virus in the deer with those circulating among the human population, the exact way it is spreading from people to deer has not been identified.

Can I get SARS-CoV-2 from deer? Important update.

The testing conducted in Ontario detected what appears to be the first case of deer to human spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Pickering et al., 2022). In the same time period that the deer samples were collected, the fall of 2021, human testing found a person that was infected with a version of the virus that very closely resembled the version found in deer. While limited details are available about the human case due to privacy considerations, we do know that the individual was also from southwestern Ontario and was known to have had close contact with deer.

It is important to note that according to Pickering et al. (2022), the mutations that are in the deer version of the virus do not appear to reduce the efficacy of human vaccines. Also, no additional human cases with this version of the virus have been detected.

According to the NDMNRF, the risk of contracting COVID-19 from a human is still many times higher than contracting it from a deer but they do advise caution for people that are in close contact with deer or deer carcasses. Below there is a link to advice on how to minimize your exposure if handling deer carcasses.

How to reduce your exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife

We encourage everyone to follow public health guidelines and the government of Canada’s advice on human-wildlife contact. Human-deer interactions are not limited to hunters, especially in suburban and exurban areas, so this doesn’t just apply to deer hunters. For example, the recommendation to wear a mask, gloves, and eye protection when handling a deer carcass applies to both hunters and someone dealing with a deer-vehicle collision.

What are the next steps for Ontario?

The NDMNRF is continuing to work with partners to test a variety of wildlife species for SARS-CoV-2. In 2020, a total of 936 samples from raccoons, skunk, mink, white-tailed deer, and various other mammals in Ontario and Quebec were collected and tested, with no positive detections (methods described in Greenhorn et al., 2021). From 2021, 298 deer samples have been tested with the results being published in Pickering et al. (2022).

The OFAH has been monitoring this situation closely and is committed to keeping our members and the hunting community informed as we learn more about the potential relationships between the virus and Ontario’s deer, other wildlife, and people.

What role can hunters play?

As mentioned above, Ontario’s confirmed cases were detected during 2021 CWD surveillance. This highlights the incredibly important role that hunters play in the monitoring and identification of disease in wildlife. Without the existing pool of hunters providing samples from their harvested deer, detection of the virus and other potential deer health risks would be much more challenging.

In addition to participating in monitoring programs like the CWD surveillance program, hunters can act as wildlife disease sentinels by reporting sick, strange-acting, or dead wildlife to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative. Even though deer do not appear to develop symptoms from SARS-CoV-2, reporting anything out of the ordinary can make a meaningful difference. Hunters have a wealth of experience with nature and wildlife that quickly allows them to distinguish the unusual from the ordinary. By reporting these events, wildlife disease threats can be identified early, which increases the chance of a successful response that safeguards both human and wildlife health.

Leave a Comment